Venture Capital for Bio 101

By: Laura Deming, GP at The Longevity Fund, with some edits & anecdotes by CelineTo make progress in a science start up you’ll likely need to do experiments. This requires money. Even if you’re fortunate enough to be able to self-finance or raise a small amount from family and friends, you may want to find a partner who can give you money and pragmatic advice, and help you raise the very large sums ($30-$300M) required to take a drug to market. Venture capitalists are investors who specifically invest in high risk, high reward companies. Venture capitalists invest capital in your company in exchange for equity, in the hope that the equity is worth significantly more in the future.

This post will cover how to find and convince such a person to swap money for equity in your new company.

Choosing who you want to work with

A good investor can help you do important things that strong networks are helpful for, like fundraising and recruiting. A good investor can also act as a strategic sounding board and source of pragmatic advice. However, you can get these things from equity advisors or mentors, so you should view them more as a way to rank investors than a reason to take venture money. How do you tell who has these characteristics?

Make a list

The first thing you should do when considering your options is to make a list of all the investors you’d like to work with. Our companies do this when fundraising. Typically it contains 50-150 funds and angel investors. You can use this list to track your pipeline in fundraising, and to keep people accountable to make warm introductions. It might be helpful to note other deals the investor has done, blog posts where they share their investment theses, variables such as fund size, the specific partner’s role in the fund, deal size and preferred ownership, and other relevant variables. Raising capital in the early stages can largely be a numbers game, so be prepared to talk to a lot of investors.

Reference check investors

Once you let an investor exchange their money for your equity, it is very hard to get rid of them. The best way to get a feel for an investor’s future behavior is to reference check their past behavior with other founders. Warm connections to their portfolio founders are best, where you can get the real story. Often, people are unwilling to say bad things in case it might get back to the investor, so discount everything you learn from a founder you don’t know a significant amount. Ask about specifics - did the company go through hard times, and how did the investor behave if so? How many introductions did they make for fundraising, partnering and recruiting? Make a list of the helpful things they’ve done for each company, and you should be able to see a good investor’s strengths and weaknesses. This is even more important if the investor will have a controlling stake in your company, or will join the board. Other sources include their social media. You can get a decent feel for the investor’s personality from how they conduct themselves online.

Ask for investor recommendations

Think of the founders you most admire, and would like to emulate. Ask them who they consider to be the best investors in your space. Particularly, ask them about specific partners at venture funds, not just for the names of good venture funds. While the brand of the firm is important, you will generally only interact with the specific partner who invests in your deal - therefore information on the specific partner is generally more telling than info on the fund as a whole.

Running the process

Pre-raise work

You’ll inevitably start off worse at pitching your company than after you’ve done a number of meetings. Why burn your first investor meetings with the worst version of your pitch? A good way to get better at pitching is literally just to practice - once you have your deck, aim to walk through it with 10-20 people. Take the pitch seriously and, more than their specific feedback, track if the person seems bored in the meeting. Your first goal with this pre-raise work is just to make sure the pitch is understandable and interesting.

The next step in the pre-raise work is to craft the different narratives you’ll tell during the raise. To find these narratives, you should line up 10-15 meetings with savvy angel investors (ideally friendly ones) to give feedback on the content of your pitch. Often, 2-3 different stories will emerge, each of which will appeal to a different type of investor. There should be a strong ‘a-ha’ moment when you find a pitch that really works, and the last tranche of investors you talk to in this stage should actually be asking to invest if the pitch is good enough.

I can’t stress how important it is to know that your pitch is actually understandable and interesting before you start the process. So many founders burn insane amounts of time kidding themselves that people get what they are saying when actually those people are just being nice. Investors are motivated to maximize optionality - to have the chance to invest if your deal gets hot, even if they don’t like it now - so they aren’t motivated to be transparent with you and tell you why they think your baby is ugly.

Make a pipeline

Fundraising is like sales. It’s a process. Make a spreadsheet or kanban with different stages, for example: leads, pending intros, intros, scheduled meeting, first meeting, first diligence questions answered, partner meeting, and term sheet. Take your list of investors from earlier and get to work pumping them into this pipeline. Take everyone in your network, set up a quick phone call with them (or a meeting if they’re likely to be very helpful), convert them with the pitch then ask for all intros they’re willing to make. Ideally some angel investors from the last tranche of pre-raise work should be helping you here. Hold people accountable to make the introductions they promise by sharing them on the investor spreadsheet.

Before you meet with an investor

Many investors make decisions based on the recommendations of trusted allies. Figuring out who those people are and pitching them before you walk in the room can be more important than the investor pitch itself. If there a few investors you really want to work with, and you have lead time before your raise, it’s worth the time required to understand who they will turn to by quizzing portfolio companies who have been through the process, then doing everything you can to get an innocuous meeting with those people where without asking for anything you simply get them excited about your company.

Timing

Raising money can take a very variable amount of time. If you have clear traction, are very good at pitching, or have someone already in the pipeline who might serve to implicitly supply competitive pressure, the raise could take 2 weeks to a term sheet. For other companies, the process might take 3 or even 6 months. Don’t despair, but do be very aware of how much runway you might need to get the process done.

Fast raises are typically characterized by doing the pre-raise work to avoid burning a significant % of meetings on just getting the pitch right, having a few people already lined up whom you’ve been cultivating as potential leads, or having a high-value (read: VCs trust their opinion on you and your company) advisor who can make many warm introductions for you at the beginning of the raise.

Slower raises typically mean you’re starting from scratch. In this case, numbers matter. Once you’ve honed your pitch, the number of people you talk to and funnel through the pipeline becomes the one variable to focus on. Figure out where people are dropping in the process and what you can do to increase conversion at that point. Make a separate pipeline for meetings with other founders or advisors to do in order to secure the warm intros you need to get higher value prospects in the pipeline.

Getting to a partner meeting

In an ideal world, you’d talk to the decision maker at a firm from day one. Usually, decision makers at a venture fund are the Partners. Many firms have internal limits on how much money someone can invest without getting the approval of others in the firm. For example, some firms allow Principals (one step below Partner) at the firm to independently write $1M checks, but not larger amounts. Associates usually cannot write checks independently. Ask about this explicitly. If the amount you are raising requires other partners to buy-in, and your point of contact at the firm is already converted, your next focus should be on getting to the partner meeting.

Once you have converted your contact at the firm, they should offer a time to schedule a meeting with their partners. Work with them to maximize the chance of a positive outcome. Make sure they deeply understand what you are doing and can answer all of the most likely objections to it. A common failure mode at this stage is failing to realize that someone may be excited about what you are doing without actually being able to coherently re-explain it. Plot with them how they will advocate for you, and go through your most common diligence questions with them. Many firms require an investor to write an investment memorandum or IM before doing a deal. Help your advocate write a great one, you will give them the best possible ammo with which to convert their partners. CLHH note: I wrote documents that functioned as the IM for my investors. If you can write a concise document on the thesis behind your company, it can be very helpful as investors are often working through multiple deals.

For the partner meeting, come in with a pitch which you can go through quickly (15 minutes) if need be, and plan to spend the majority of the time answering questions. You should get an answer on whether you’re likely to get a term sheet directly after a partner meeting, although it might take the firm a few days to craft it.

The different types of raises

The set of possible terms for a raise is literally infinite! However, social norms and the ways in which investors have previously been burned constrain what is viable. Here are descriptions of two common formats.

Party Round: A round with no lead. Instead of looking for a lead investor to set the terms of the raise, and then filling up the rest of the round with smaller investors, you instead get a bunch of smaller checks from minor and angel investors to come in all at once. This is typically only feasible at the seed stage. An example might be raising $1-3M with a set of $500K-$100K checks on an financial instrument that doesn’t give a lot of control to the investors and pushes some of the financial negotiation down the road (for example, a SAFE or convertible note).

Seed round w/ lead: A round with terms negotiated by a lead or co-leads. This will typically be a priced round, in which you finalize how many shares you are selling for the money you get, and potentially give up some control to the investor. An example might be a fund investing $3M of $5M, and filling out the rest of the amount with $100-$1M checks from smaller investors.

Priced round: In a priced round, you sell shares in your company. If you raise a larger round (usually greater than $2M, although it varies by investor, geography, and industry), you will likely raise via a priced round. Priced rounds require significant legal work, and you pay both yours and likely your lead investor’s legal fees. Expect an early financing to cost around $50,000 in total. You will only get a term sheet if you raise via a priced round.

SAFEs: Often, smaller rounds are raised on a financial document called a SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity). A SAFE allows you to take capital now without explicitly pricing your company. You can take capital via a SAFE quickly and easily, unlike priced rounds where all investors wire at the same time.

Negotiating terms (Priced Round)

Knowing the market

It’s hard to negotiate if you don’t have leverage. Ideally, you can play multiple competing term sheets off of each other to get better terms. Knowing the market is also important. If most comparable companies you are aware of received $10M pre-money valuations (a number used to determine how much equity the investor will get in return for the money), but someone offers you a $5M pre-money valuation (a cheaper price, and better deal for the investor), you can directly call them out on it. In the same way that checking Amazon for the cheapest price of an item might allow you to negotiate a better in-store purchase, knowing what valuation you might ‘expect’ is important. This will be a less effective tactic if you are at the end of your raise and the investor knows you don’t have other options, so it’s ideal to run a tight process and stack investor meetings when you do go out.

Some terms to care about

Financial and control terms are the two things you’re negotiating in a term sheet.

Financial = How much money you’re going to get, and how much money or other capital you’re going to give back to an investor in exchange in different outcome scenarios. It’s important to note that this extends beyond just how much equity they have - certain terms mandate that you pay an investor back some multiple of their capital invested before you get paid, independent of what fraction of the company they own (liquidation preference is one term to look out for).

Control = How much control the investor has of the company. This can be related to, but not dependent on how much of the company they own. Typically, you will make a new type of shares for an incoming investor, and assign that type of shares certain rights. Within that type, the relative ownership of different investors and their decisions will determine what that type of shares will vote to do, so track investor dynamics (which investors are allies on which topics) and what subset of investors would have to vote together to pass certain resolutions.

Financial terms can include those noted below. A critical first step when you receive a term sheet is to construct a cap table (a spreadsheet with the current ownership percentages of company vs investor stock owners, and projected future ownership and financial return given different exit scenarios). This should include an option pool (stocks you plan to issue to future employees). Calculate out, given the term sheet, what the financial return will be to you vs the investors in different exit scenarios. This is often confusing to do for a first-time founder, but it is a critical step..

Amount to be invested: How much $ will go into the company. Typically this specifies how much you will raise in total, and the amount of that which the lead investor is planning to put in. The rest you should plan to fill out with other investors, with their help.

Note on raising SAFEs/debt: If you are doing a financing on a debt-like instrument (for example, a convertible note or a SAFE), you’ll care about the valuation cap and discount instead of the below terms, which are for a priced round. When you take on debt in this context, you’re getting capital today and saying ‘I’ll pay you back with some stocks from my company in the future, when someone else invests’. The cap and discount determine how many stocks you will give the convertible note or SAFE holder at that future point. The cap number typically means, if the pre-money valuation for the next round is higher than the cap, the investor is given shares as though they invested with the cap as the pre-money valuation. If the pre-money valuation for the next round is lower than the cap, the investor will get a number of shares as though they invested at the lower valuation (a better deal for them). The discount means the investor gets a discounted price per share to the next round. Both or either may be included as terms for one of these instruments.

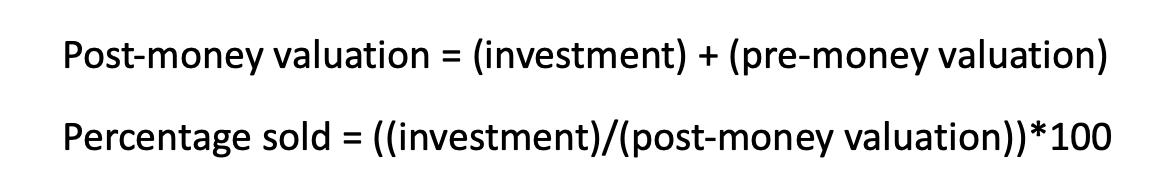

Valuation: the amount of money your company is worth. This is usually the biggest variable in a term sheet and determines how much of your company you sell to get the investment.

Post-money valuation: The value of your company after all the investment is taken. This number, divided by the amount invested, is the percentage of the company you will be selling to the investors.

A term sheet can dictate either a pre-money or post-money valuation. If the pre-money is fixed, the post-money increases with the amount you raise. If you have a fixed post-money, the pre-money lowers as you raise more. The latter can be good if you plan to raise less; if you oversubscribe, you may end up selling more of your company than originally intended.

Option pool: The option pool is the common shares reserved for allocating for employees. Generally speaking, the option pool comes from the founder’s shares. An investor can request an increase in the number of shares in the option pool and this can warp the concepts described above. If so, it is important to figure out whether this increase will implicitly be done before the financing.

How the option pool impacts how much you sell of your company: If the post-money valuation and amount to invest are fixed, then adding options means the pre-money valuation implicitly goes down and thus the shares you own are implicitly worth less $ than they otherwise would be. If the pre-money and amount to invest are fixed, and options are added, then the post-money of the round will go up, and investors will receive a smaller percentage of the company for their capital. In both cases, your percentage ownership will go down, but it is good to ensure you have sufficient options to entice strong future employees.

Liquidity preference: This is a fancy way of saying, when you sell or exit your company, how many times over you have to pay back your investors before you get paid. 1x means they get their money back first, but higher multiples than this mean they actually make some fixed return before you get paid.

Participating preferred: This means that, in addition to getting some fixed multiple on their money, investors participate in the upside to an exit proportional to their ownership.

Anti-dilution: If you have a subsequent round at a lower price, anti-dilution will adjust the ownership your investors have at your expense.

Go through the term sheet with your lawyer to suss out any other relevant variables - this is just a high-level overview.

Control terms can include control over an exit (forcing the sale of a company or deciding whether to do an IPO), the ability to block a subsequent financing, information rights (what information you’re obliged to supply the investors, on what schedule), and many other parameters.

Board of Directors

One important component of the control terms is who gets to decide the composition of the Board of Directors, and what things the Board of Directors can control with different voting thresholds. Technically, this is a body which is supposed to act in the best interests of company shareholders. Investors normally have certain rights whether they are on the board or not. You should keep track of which rights they investors have through the type of stock they own, and which rights they have through their vote on the board of directors. Typically, these two rights will be voted on differently - as a founder, you may control the board of directors, but unless you personally invest in the round you won’t be able to control what a type of shares issued to investors vores do.

Books like Venture Deals can be a good comprehensive glossary to decrypt what a term sheet is really saying.

Post-term sheet process

After you get and sign a term sheet, you should budget up to a month to complete diligence items (investors may ask a lawyer to review literally all the corporate documents you’ve accumulated to date, and in biotech there may be specific diligence around, for example, the feasibility of manufacturing your drug and IP protection on your lead drug).

The term sheet is not equivalent to the financing documents you will eventually sign - they only spell out the major terms. For examples of what these might look like for a seed round, see Cooley’s Series Seed documents. These typically include a share purchase agreement, investor rights agreement, voting agreement, and right of first refusal agreement. These documents can be quite long (30+ pages) but are important to review with your lawyers as the way they implement concepts in the term sheet may drastically change the scope of those terms. A quick hack to see all current terms which apply to shareholders of your company is to look at your charter or articles of incorporation.

Closing the financing

Time to get money in the bank! Once you’ve negotiated the final terms of the financing with your lead investors and circulated to all investors along with the closing date in advance, you or your lawyers can circulate wiring information for your company’s bank account and collect signatures from all investors. Typically, especially for seed rounds, there will be some variability in wiring times, but everyone should wire by the close deadline.

If you have raised via a SAFE, there will likely be minimal lawyers involved and the capital can we wired once both parties have signed the document.

Post-investment management

Investor updates

Everyone talks about investor updates, but very few companies actually send them six months after they say they will. They’re not technically critical for anything and are usually in addition to the information rights in your financing docs. Typically, I’ve found it’s a biomarker of good health if a company consistently sends investor updates. They should contain key specs (cash in the bank, current burn, projected cash-out date, any revenue), progress in the last month, what investors can help with, and any fun news or pictures from the lab that might make them more memorable. It’s useful to keep investors appraised of how you are doing if you would like them to keep you top of mind (although there might be cases where you don’t want to do this).

Many companies skip the update one month, get really stressed about it, then turn them into ‘bi-monthly’, then ‘quarterly’, then ‘annual’ updates. It’s fine if you skip one or two - just get back into the train, don’t fall off it. Investors see this all the time. Don’t pretend, just get back to sending them regularly.

The next round

Many times, just as you close one round of financing, you’ll start thinking about the next. It can be useful to make a list of investors you’d like to work with in your next financing and plan update meetings with them on your progress over the years in advance of that next raise. Do note that every time you meet with an investor

Managing your investors

Your seed round may or may not include someone joining your board of directors. If so, you’ll need to plan board meetings. Typically, these include a subset of the following - an update from the company on progress to date, passing any critical resolutions, discussion of strategy, new hires and any major purchases, compensation, any HR issues, and if the board is large enough an executive session with non-company members on the performance of the CEO and any other relevant items. Coordinate with your board on major decisions in advance - no one likes to be surprised with a call for big decisions in the meeting without earlier context.

More generally, I think people underweight the value of keeping your investors in the loop, especially for small but memorable milestones. One of our companies drove a truck full of critical samples from Denver to Oakland, and asked if we could come help unload them. It was fun, and a big moment for them to celebrate the creation of their first in-house biobank. Some investors genuinely enjoy getting to help portfolio companies. No better way to find out than by asking.